You Only Click Twice: FinFisher’s Global Proliferation

This post describes the results of a comprehensive global Internet scan for the command and control servers of FinFisher’s surveillance software. It also details the discovery of a campaign using FinFisher in Ethiopia used to target individuals linked to an opposition group. Additionally, it provides examination of a FinSpy Mobile sample found in the wild, which appears to have been used in Vietnam.

Summary of Key Findings

- We have found command and control servers for FinSpy backdoors, part of Gamma International’s FinFisher “remote monitoring solution,” in a total of 25 countries: Australia, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Canada, Czech Republic, Estonia, Ethiopia, Germany, India, Indonesia, Japan, Latvia, Malaysia, Mexico, Mongolia, Netherlands, Qatar, Serbia, Singapore, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, Vietnam.

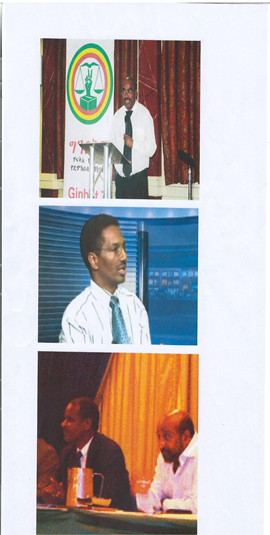

- A FinSpy campaign in Ethiopia uses pictures of Ginbot 7, an Ethiopian opposition group, as bait to infect users. This continues the theme of FinSpy deployments with strong indications of politically-motivated targeting.

- There is strong evidence of a Vietnamese FinSpy Mobile Campaign. We found an Android FinSpy Mobile sample in the wild with a command & control server in Vietnam that also exfiltrates text messages to a local phone number.

- These findings call into question claims by Gamma International that previously reported servers were not part of their product line, and that previously discovered copies of their software were either stolen or demo copies.

1. Background and Introduction

FinFisher is a line of remote intrusion and surveillance software developed by Munich-based Gamma International GmbH. FinFisher products are marketed and sold exclusively to law enforcement and intelligence agencies by the UK-based Gamma Group.1 Although touted as a “lawful interception” suite for monitoring criminals, FinFisher has gained notoriety because it has been used in targeted attacks against human rights campaigners and opposition activists in countries with questionable human rights records.2

In late July 2012, we published the results of an investigation into a suspicious e-mail campaign targeting Bahraini activists.3 We analyzed the attachments and discovered that they contained the FinSpy spyware, FinFisher’s remote monitoring product. FinSpy captures information from an infected computer, such as passwords and Skype calls, and sends the information to a FinSpy command & control (C2) server. The attachments we analyzed sent data to a command & control server inside Bahrain.

This discovery motivated researchers to search for other command & control servers to understand how widely FinFisher might be used. Claudio Guarnieri at Rapid7 (one of the authors of this report) was the first to search for these servers. He fingerprinted the Bahrain server and looked at historical Internet scanning data to identify other servers around the world that responded to the same fingerprint. Rapid7 published this list of servers, and described their fingerprinting technique. Other groups, including CrowdStrike andSpiderLabs also analyzed and published reports on FinSpy.

Immediately after publication, the servers were apparently updated to evade detection by the Rapid7 fingerprint. We devised a different fingerprinting technique and scanned portions of the internet. We confirmed Rapid7’s results, and also found several new servers, including one inside Turkmenistan’s Ministry of Communications. We published our list of servers in late August 2012, in addition to an analysis of mobile phone versions of FinSpy. FinSpy servers were apparently updated again in October 2012 to disable this newer fingerprinting technique, although it was never publicly described.

Nevertheless, via analysis of existing samples and observation of command & control servers, we managed to enumerate yet more fingerprinting methods and continue our survey of the internet for this surveillance software. We describe the results in this post.

Civil society groups have found cause for concern in these findings, as they indicate the use of FinFisher products by countries like Turkmenistan and Bahrain with problematic records on human rights, transparency, and rule of law. In an August 2012 response to a letter from UK-based NGO Privacy International, the UK Government revealed that at some unspecified time in the past, it had examined a version of FinSpy, and communicated to Gamma that a license would be required to export that version outside of the EU. Gamma has repeatedly denied links to spyware and servers uncovered by our research, claiming that the servers detected by our scans are “not … from the FinFisher product line.”4 Gamma also claims that the spyware sent to activists in Bahrain was an “old” demonstration version of FinSpy, stolen during a product presentation.

In February 2013, Privacy International, the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, Bahrain Watch, and Reporters Without Borders filed a complaint with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), requesting that this body investigate whether Gamma violated OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises by exporting FinSpy to Bahrain. The complaint called previous Gamma statements into question, noting that at least two different versions (4.00 and 4.01) of FinSpy were found in Bahrain, and that Bahrain’s server was a FinFisher product and was likely receiving updates from Gamma. This complaint, as laid out by Privacy International states that Gamma:

According to recent reporting, German Federal Police appear to have plans to purchase and use the FinFisher suite of tools domestically within Germany.5 Meanwhile, findings by our group and others continue to illustrate the global proliferation of FinFisher’s products. Research continues to uncover troubling cases of FinSpy in countries with dismal human rights track records, and politically repressive regimes. Most recently, work by Bahrain Watchhas confirmed the presence of a Bahraini FinFisher campaign, and further contradicted Gamma’s public statements. This post adds to the list by providing an updated list of FinSpy Command & Control servers, and describing the FinSpy malware samples in the wild which appear to have been used to target victims in Ethiopia and Vietnam.

We present these updated findings in the hopes that we will further encourage civil society groups and competent investigative bodies to continue their scrutiny of Gamma’s activities, relevant export control issues, and the issue of the global and unregulated proliferation of surveillance malware.

2. FinFisher: Updated Global Scan

Around October 2012, we observed that the behavior of FinSpy servers began to change. Servers stopped responding to our fingerprint, which had exploited a quirk in the distinctive FinSpy wire protocol. We believe that this indicates that Gamma either independently changed the FinSpy protocol, or was able to determine key elements of our fingerprint, although it has never been publicly revealed.

In the wake of this apparent update to FinSpy command & control servers, we devised a new fingerprint and conducted a scan of the internet for FinSpy command & control servers. This scan took roughly two months and involved sending more than 12 billion packets. Our new scan identified a total of 36 FinSpy servers, 30 of which were new and 6 of which we had found during previous scanning. The servers operated in 19 different countries. Among the FinSpy servers we found, 7 were in countries we hadn’t seen before.

In our most recent scan, 16 servers that we had previously found did not show up. We suspect that after our earlier scans were published the operators moved them. Many of these servers were shut down or relocated after the publication of previous results, but before the apparent October 2012 update. We no longer found FinSpy servers in 4 countries where previous scanning identified them (Brunei, UAE, Latvia, and Mongolia). Taken together, FinSpy servers are currently, or have been present, in 25 countries.

Importantly, we believe that our list of servers is incomplete due to the large diversity of ports used by FinSpy servers, as well as other efforts at concealment. Moreover, discovery of a FinSpy command and control server in a given country is not a sufficient indicator to conclude the use of FinFisher by that country’s law enforcement or intelligence agencies. In some cases, servers were found running on facilities provided by commercial hosting providers that could have been purchased by actors from any country.

The table below shows the FinSpy servers detected in our latest scan. We list the full IP address of servers that have been previously publicly revealed. For active servers that have not been publicly revealed, we list the first two octets only. Releasing complete IP addresses in the past has not proved useful, as the servers are quickly shut down and relocated.

| IP | Operator | Routed to Country |

|---|---|---|

| 117.121.xxx.xxx | GPLHost | Australia |

| 77.69.181.162 | Batelco ADSL Service | Bahrain |

| 180.211.xxx.xxx | Telegraph & Telephone Board | Bangladesh |

| 168.144.xxx.xxx | Softcom, Inc. | Canada |

| 168.144.xxx.xxx | Softcom, Inc. | Canada |

| 217.16.xxx.xxx | PIPNI VPS | Czech Republic |

| 217.146.xxx.xxx | Zone Media UVS/Nodes | Estonia |

| 213.55.99.74 | Ethio Telecom | Estonia |

| 80.156.xxx.xxx | Gamma International GmbH | Germany |

| 37.200.xxx.xxx | JiffyBox Servers | Germany |

| 178.77.xxx.xxx | HostEurope GmbH | Germany |

| 119.18.xxx.xxx | HostGator | India |

| 119.18.xxx.xxx | HostGator | India |

| 118.97.xxx.xxx | PT Telkom | Indonesia |

| 118.97.xxx.xxx | PT Telkom | Indonesia |

| 103.28.xxx.xxx | PT Matrixnet Global | Indonesia |

| 112.78.143.34 | Biznet ISP | Indonesia |

| 112.78.143.26 | Biznet ISP | Indonesia |

| 117.121.xxx.xxx | Iusacell PCS | Malaysia |

| 201.122.xxx.xxx | UniNet | Mexico |

| 164.138.xxx.xxx | Tilaa | Netherlands |

| 164.138.28.2 | Tilaa | Netherlands |

| 78.100.57.165 | Qtel – Government Relations | Qatar |

| 195.178.xxx.xxx | Tri.d.o.o / Telekom Srbija | Serbia |

| 117.121.xxx.xxx | GPLHost | Singapore |

| 217.174.229.82 | Ministry of Communications | Turkmenistan |

| 72.22.xxx.xxx | iPower, Inc. | United States |

| 166.143.xxx.xxx | Verizon Wireless | United States |

| 117.121.xxx.xxx | GPLHost | United States |

| 117.121.xxx.xxx | GPLHost | United States |

| 117.121.xxx.xxx | GPLHost | United States |

| 117.121.xxx.xxx | GPLHost | United States |

| 183.91.xxx.xxx | CMC Telecom Infrastructure Company | Vietnam |

Several of these findings are especially noteworthy:

- Eight servers are hosted by provider GPLHost in various countries (Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, US). However, we observed only six of these servers active at any given time, suggesting that some IP addresses may have changed during our scans.

- A server identified in Germany has the registrant “Gamma International GmbH,” and the contact person is listed as “Martin Muench.”

- There is a FinSpy server in an IP range registered to “Verizon Wireless.” Verizon Wireless sells ranges of IP addresses to corporate customers, so this is not necessarily an indication that Verizon Wireless itself is operating the server, or that Verizon Wireless customers are being spied on.

- A server in Qatar that was previously detected by Rapid7 seems to be back online after being unresponsive during the last round of our scanning. The server is located in a range of 16 addresses registered to “Qtel – Corporate accounts – Government Relations.” The same block of 16 addresses also contains the websitehttp://qhotels.gov.qa/.

3. Ethiopia and Vietnam: In-depth Discussion of New Samples

3.1 FinSpy in Ethiopia

We analyzed a recently acquired malware sample and identified it as FinSpy. The malware uses images of members of the Ethiopian opposition group, Ginbot 7, as bait. The malware communicates with a FinSpy Command & Control server in Ethiopia, which was first identified by Rapid7 in August 2012. The server has been detected in every round of scanning, and remains operational at the time of this writing. It can be found in the following address block run by Ethio Telecom, Ethiopia’s state-owned telecommunications provider:

The server appears to be updated in a manner consistent with other servers, including servers in Bahrain and Turkmenistan.

| MD5 | 8ae2febe04102450fdbc26a38037c82b |

| SHA-1 | 1fd0a268086f8d13c6a3262d41cce13470886b09 |

| SHA-256 | ff6f0bcdb02a9a1c10da14a0844ed6ec6a68c13c04b4c122afc559d606762fa |

The sample is similar to a previously analyzed sample of FinSpy malware sent to activists in Bahrain in 2012. Just like Bahraini samples, the malware relocates itself and drops a JPG image with the same filename as the sample when executed by an unsuspecting user. This appears to be an attempt to trick the victim into believing the opened file is not malicious. Here are a few key similarities between the samples:

- The PE timestamp “2011-07-05 08:25:31” of the packer is exactly the same as the Bahraini sample.

- The following string (found in a process infected with the malware), self-identifies the malware and is similar to strings found in the Bahraini samples:

- The samples share the same Bootkit, SHA-256: ba21e452ee5ff3478f21b293a134b30ebf6b7f4ec03f8c8153202a740d7978b2.

- The samples share the same driverw.sys file, SHA-256: 62bde3bac3782d36f9f2e56db097a4672e70463e11971fad5de060b191efb196.

Figure 2. The image shown to the victim contains pictures of members of the Ginbot 7 Ethiopian opposition group

In this case the picture contains photos of members of the Ethiopian opposition group, Ginbot 7. Controversially, Ginbot 7 was designated a terrorist group by the Ethiopian Government in 2011. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and Human Rights watch have both criticized this action, CPJ has pointed out that it is having a chilling effect on legitimate political reporting about the group and its leadership.

The existence of a FinSpy sample that contains Ethiopia-specific imagery, and that communicates with a still-active command & control server in Ethiopia strongly suggests that the Ethiopian Government is using FinSpy.

3.2 FinSpy Mobile in Vietnam

We recently obtained and analyzed a malware sample6 and identified it as FinSpy Mobile for Android. The sample communicates with a command & control server in Vietnam, and exfiltrates text messages to a Vietnamese telephone number.

The FinFisher suite includes mobile phone versions of FinSpy for all major platforms including iOS, Android, Windows Mobile, Symbian and Blackberry. Its features are broadly similar to the PC version of FinSpy identified in Bahrain, but it also contains mobile-specific features such as GPS tracking and functionality for silent ‘spy’ calls to snoop on conversations near the phone. An in-depth analysis of the FinSpy Mobile suite of backdoors was provided in an earlier blog post: The Smartphone Who Loved Me: FinFisher Goes Mobile?

| MD5 | 573ef0b7ff1dab2c3f785ee46c51a54f |

| SHA-1 | d58d4f6ad3235610bafba677b762f3872b0f67cb |

| SHA-256 | 363172a2f2b228c7b00b614178e4ffa00a3a124200ceef4e6d7edb25a4696345 |

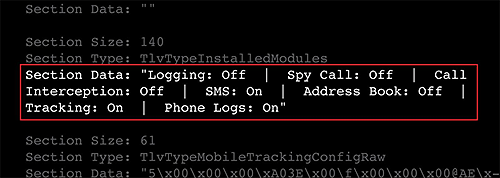

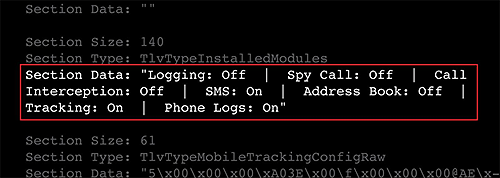

The sample included a configuration file7 that indicates available functionality, and the options that have been enabled by those deploying it:

Figure 3. Image of a section of a configuration file for the FinSpy Mobile sample

Figure 3. Image of a section of a configuration file for the FinSpy Mobile sample

Interestingly, the configuration file also specifies a Vietnamese phone number used for SMS based command and control:

The command and control server is in a range provided by the CMC Telecom Infrastructure Company in Hanoi:

This server was active until very recently and matched our signatures for a FinSpy command and control server. Both the command & control server IP and the phone number used for text-message exfiltration are in Vietnam which indicates a domestic campaign.

This apparent FinSpy deployment in Vietnam is troubling in the context of recent threats against online free expression and activism. In 2012, Vietnam introduced new censorship laws amidst an ongoing harassment, intimidation, and detention campaign against of bloggers who spoke out against the regime. This culminated in the trial of 17 bloggers, 14 of whom were recently convicted and sentenced to terms ranging from 3 to 13 years.8

4. Brief Discussion of Findings

Companies selling surveillance and intrusion software commonly claim that their tools are only used to track criminals and terrorists. FinFisher, VUPEN and Hacking Team have all used similar language.9 Yet a growing body of evidence suggests that these tools are regularly obtained by countries where dissenting political activity and speech is criminalized. Our findings highlight the increasing dissonance between Gamma’s public claims that FinSpy is used exclusively to track “bad guys” and the growing body of evidence suggesting that the tool has and continues to be used against opposition groups and human rights activists.

While our work highlights the human rights ramifications of the mis-use of this technology, it is clear that there are broader concerns. A global and unregulated market for offensive digital tools potentially presents a novel risk to both national and corporate cyber-security. On March 12th, US Director of National Intelligence James Clapper stated in his yearly congressional report on security threats:

“…companies develop and sell professional-quality technologies to support cyberoperations–often branding these tools as lawful-intercept or defensive security research products. Foreign governments already use some of these tools to target U.S. systems.”

The unchecked global proliferation of products like FinFisher makes a strong case for policy debate about surveillance software and the commercialization of offensive cyber-capabilities.

Our latest findings give an updated look at the global proliferation of FinSpy. We identified 36 active FinSpy command & control servers, including 30 previously-unknown servers. Our list of servers is likely incomplete, as some FinSpy servers employ countermeasures to prevent detection. Including servers discovered last year, we now count FinSpy servers in 25 countries, including countries with troubling human rights records. This is indicative of a global trend towards the acquisition of offensive cyber-capabilities by non-democratic regimes from commercial Western companies.

The Vietnamese and Ethiopian FinSpy samples we identified warrant further investigation, especially given the poor human rights records of these countries. The fact that the Ethiopian version of FinSpy uses images of opposition members as bait suggests it may be used for politically influenced surveillance activities, rather than strictly law enforcement purposes.

The Ethiopian sample is the second FinSpy sample we have discovered that communicates with a server we identified by scanning as a FinSpy command & control server. This further validates our scanning results, and calls into question Gamma’s claim that such servers are “not … from the FinFisher product line.”10 Similarities between the Ethiopian sample and those used to target Bahraini activists also bring into question Gamma International’s earlier claims that the Bahrain samples were stolen demonstration copies.

While the sale of such intrusion and surveillance software is largely unregulated, the issue has drawn increased high-level scrutiny. In September of last year, the German foreign minister, Guido Westerwelle, called for an EU-wide ban on the export of such surveillance software to totalitarian states.11 In a December 2012 interview, Marietje Schaake (MEP), currently the rapporteur for the first EU strategy on digital freedom in foreign policy, stated that it was “quite shocking” that Europe companies continue to export repressive technologies to countries where the rule of law is in question.12

We urge civil society groups and journalists to follow up on our findings within affected countries. We also hope that our findings will provide valuable information to the ongoing technology and policy debate about surveillance software and the commercialisation of offensive cyber-capabilities.

0 comments: